Summary

In continuation of the COVID-19 survey series launched by The Center for Social and Behavioral Science, the present article investigates how Illinoisians of different key demographics perceive COVID-19 and mobile technologies. The present analysis focused specifically on age, race, gender, education, and urban/rural setting. Furthermore, the article highlights potential challenges as well as opportunities for promoting the adoption of COVID-19 mobile applications.

Attitudes Towards Technology

Willingness to use COVID-19 technology

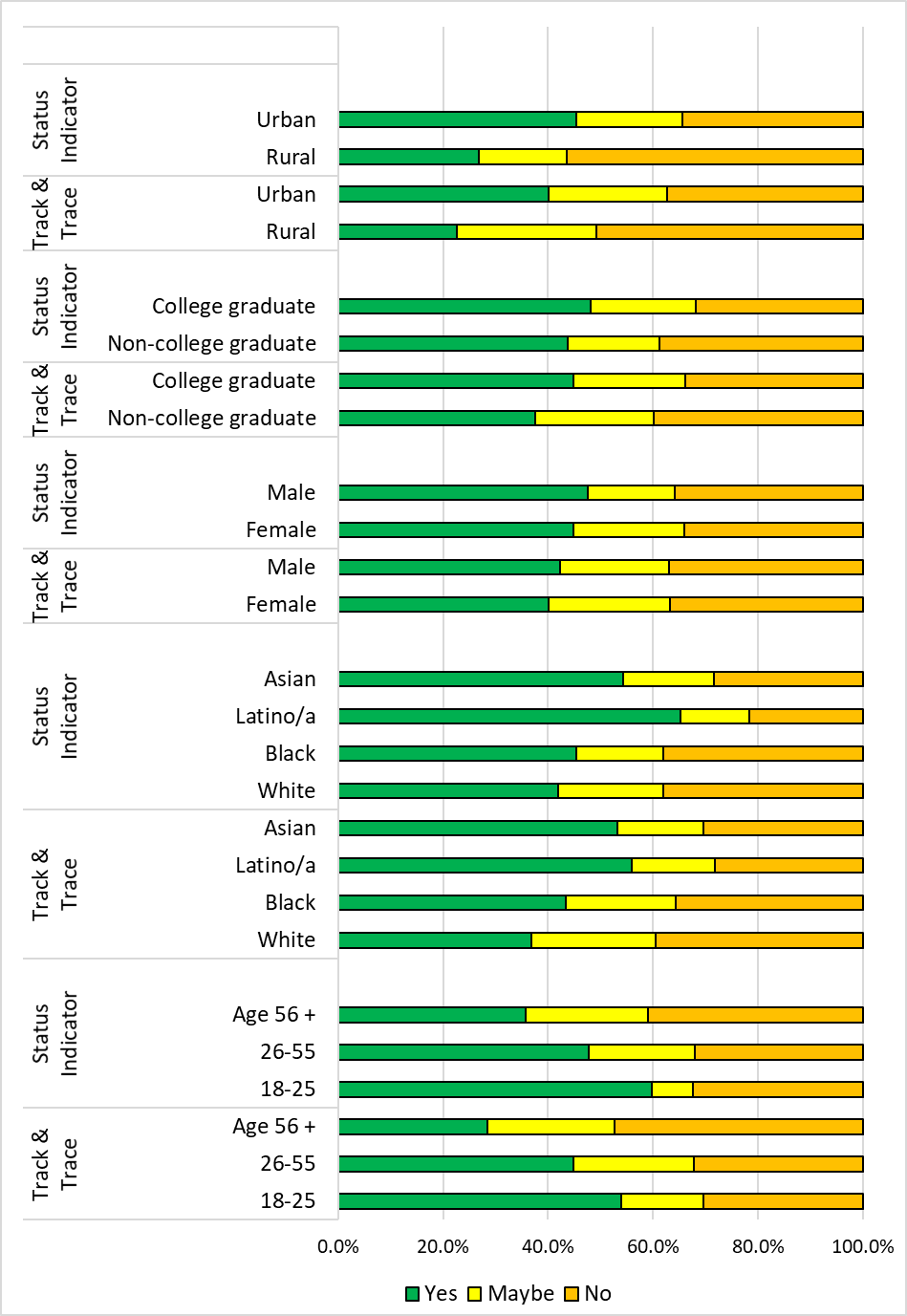

Generally speaking, geography, age, and race appeared to influence the willingness to utilize either track-and-trace or status indicator COVID-19 mobile applications (see Figure 1).

Rural/urban setting. Regarding the geographic setting, 40.1% of the respondents living in urban areas said they would be willing to use a track-and-trace app, while only 22.5% of those in rural settings said the same – the lowest percentage of any demographic group. Looking specifically at those living in rural areas who own a smartphone (84.5%), willingness to use a track-and-trace app was nearly identical (22.0%). These findings suggest that rural-urban differences in willingness to utilize COVID-19 mobile technology are not merely due to differences in mobile phone access. Thus, rural areas may require a different approach to designing persuasive messages to encourage their use of COVID-19 mobile technology.

College education. Regarding education, individuals with at least a college degree were 7% more likely than those without a college degree to be willing to use track-and-trace technology (45% vs 38%).

Gender. There was very little difference between men and women’s willingness to use COVID-19 technology. A mere 2% more of men than women reported that they would use a track-and-trace app (42% vs. 40%).

Race. Regarding race, Latinos were the most willing to utilize COVID-19 mobile applications (56% yes), followed by Asians (53%), Blacks (43%), and then Whites (37%). These results dovetail with past work from the Pew Research Center, which suggests that Latino populations may be more trusting of mobile phone technology such as track-and-trace apps that could be used to combat COVID-19 (Anderson & Auxier 2020).

Age. Only 28.5% of those 56 years and older indicated they would be willing to use a track-and-trace app, compared to 44.9% of those 26-55 and 53.9% of those 18-25. Among those 56 years and older who also own a smartphone (89%), attitudes toward using a track-and-trace app were only a couple percentage points higher (30.8%), indicating that the major barrier to adoption is likely not access to a smartphone itself. Similar differences were observed for willingness to use a status indicator app.

Figure 1: Would you be willing to use [COVID-19 App] by region type, education, sex, race, and age.

Qualitatively, participants expressed concern for their loss of privacy. Despite this concern, men and women both recognized that the ability to prevent future cases and protect their loved ones from COVID-19 would make a COVID-19 mobile app worth adopting. The only gender difference revealed from open-ended responses was that some women believed the COVID-19 technology might inadvertently lead to discrimination against those who have tested positive for COVID-19. This is an interesting finding that should be explored in future research.

Factors Shaping Adoption

Our previous analysis showed that about 7 in 10 individuals believed that the organization offering the potential app would influence their likelihood to utilize the technology. In the present analysis, we build on those findings by examining factors that may shape whether those from a different age, race, gender, education level, and location (rural vs. urban location) would utilize mobile app technology to combat COVID-19.

Institutional trust

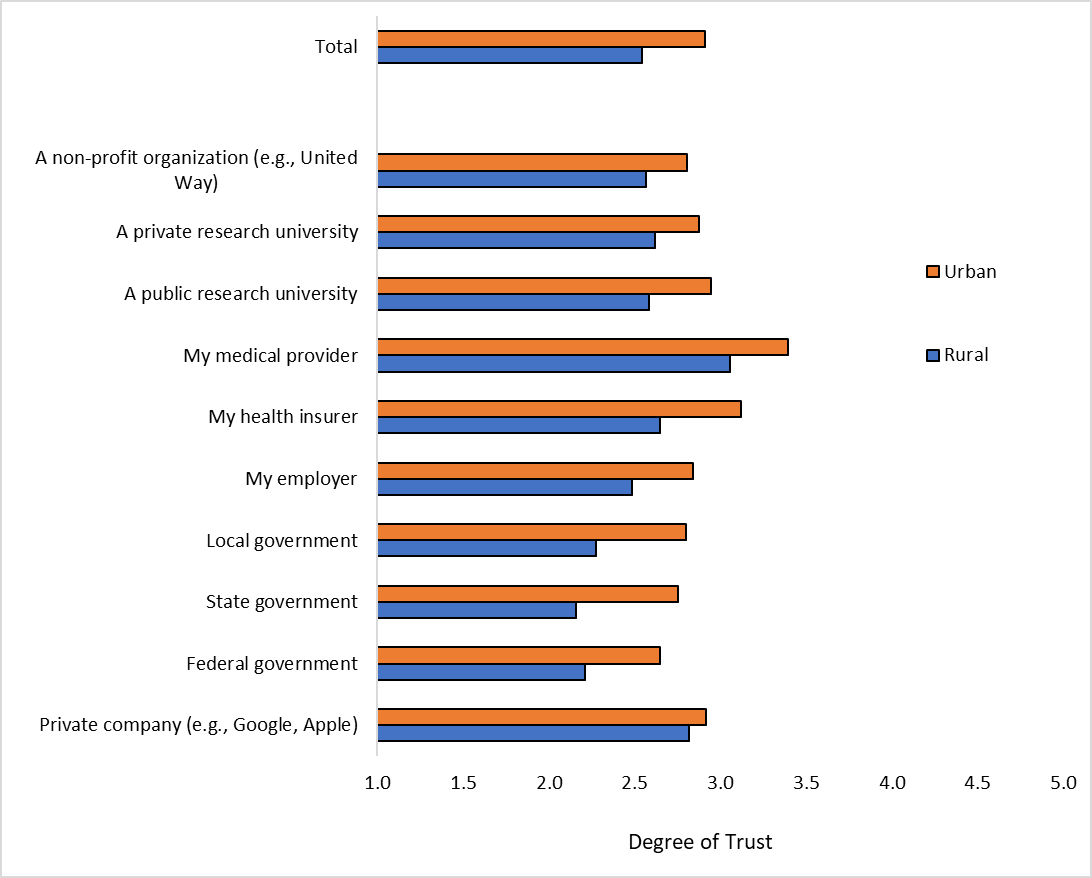

Rural/urban setting. On average, respondents in urban areas reported substantially greater amounts of trust than those in rural areas (see Figure 2). The largest differences were among local (M=2.80 vs. M=2.28) and state (M=2.75 vs. M=2.16) governments. Interestingly, the smallest difference (M=2.92 vs. M=2.82) was among private companies like Google and Apple. This overwhelming lack of trust of rural respondents could be one of the primary motivating factors behind their lower willingness to use COVID-19 mobile technologies.

Figure 2: If such a COVID-19 status app were offered, who would you trust to protect your privacy?

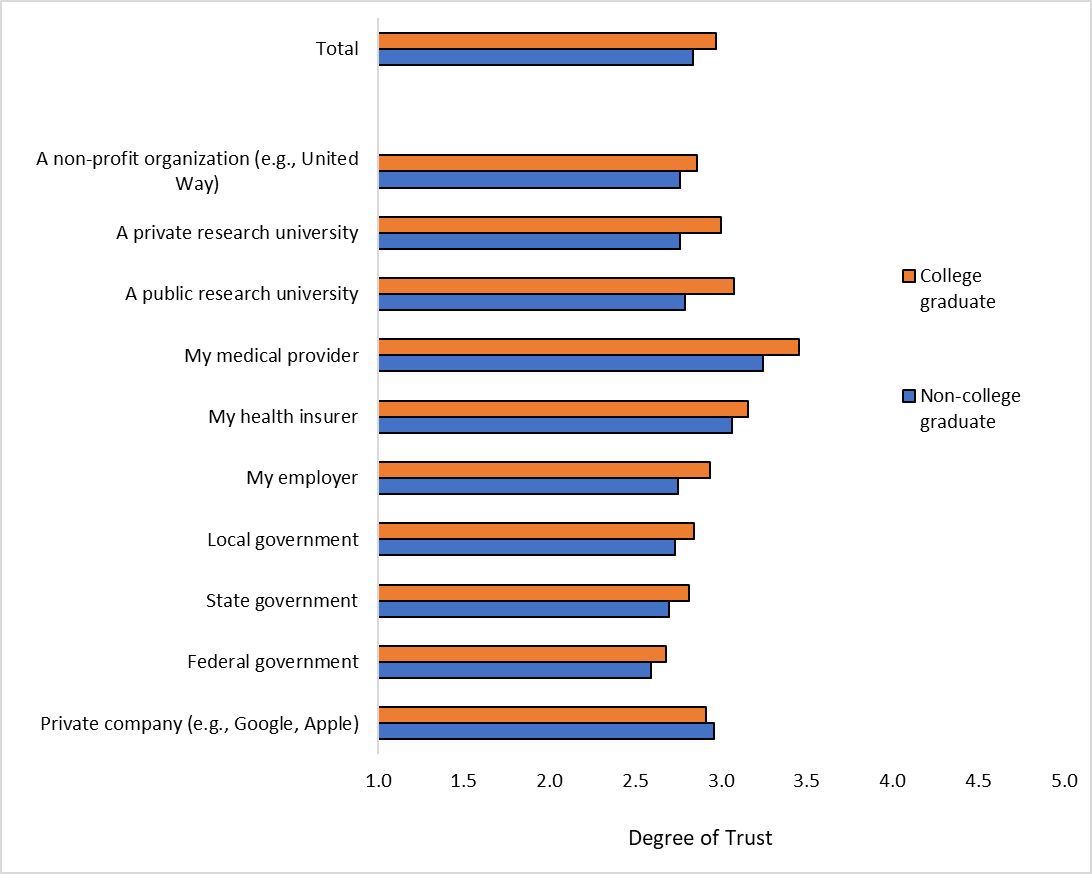

College education. Individuals with a 4-year college degree had more trust across all organizations than those without a 4-year college degree (M=2.97 vs. M=2.84) (see Figure 3). This general trend held except for private companies, although the difference, in this case, is minimal. Perhaps not surprisingly, the largest differences in trust were observed for private (M=3.00 vs. M=2.76) and public (M=2.08 vs. M=2.79) research universities, with those with a college degree being more trustworthy of these educational institutions than those without it.

Figure 3: If such a COVID-19 status app were offered, who would you trust to protect your privacy?

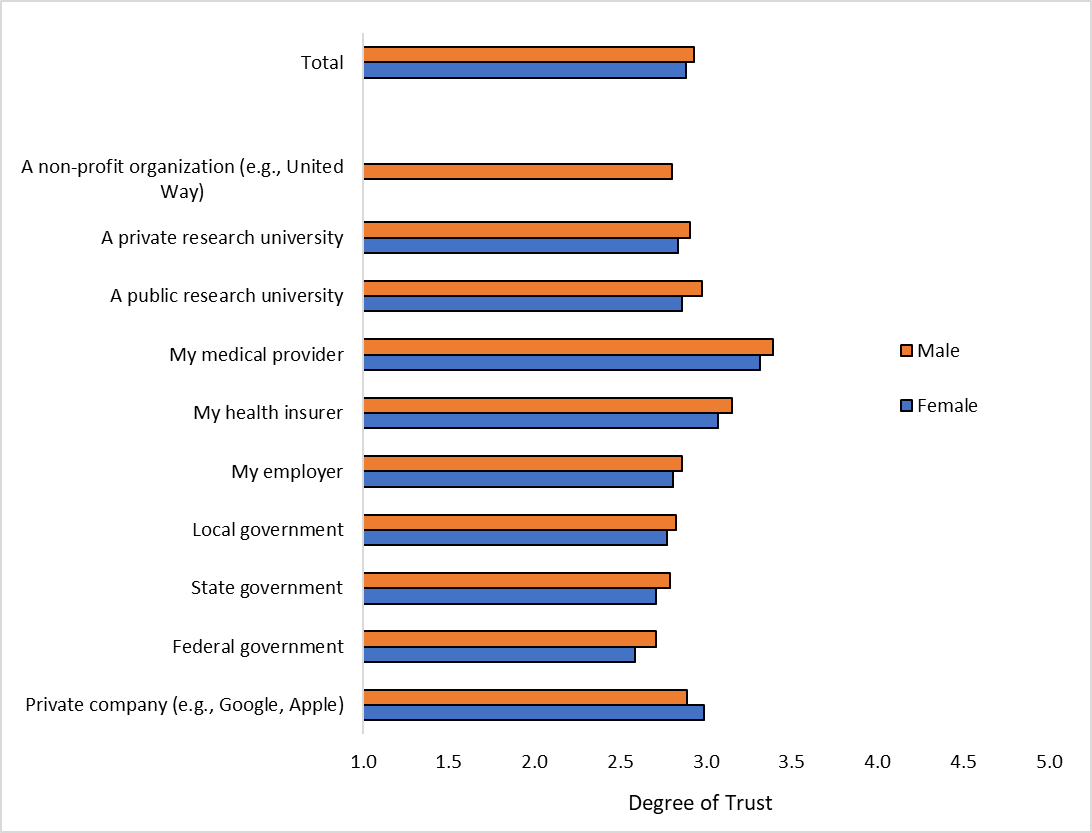

Gender. Gender was not substantially associated with differential trust across institutions, though men were slightly more trusting of almost all organizations relative to women (M=2.93 vs. M=2.87) (see Figure 4). The sole exception was private companies, which women reported slightly more trust in than men to protect their privacy (M=2.99 vs. M=2.89).

Figure 4: If such a COVID-19 status app were offered, who would you trust to protect your privacy?

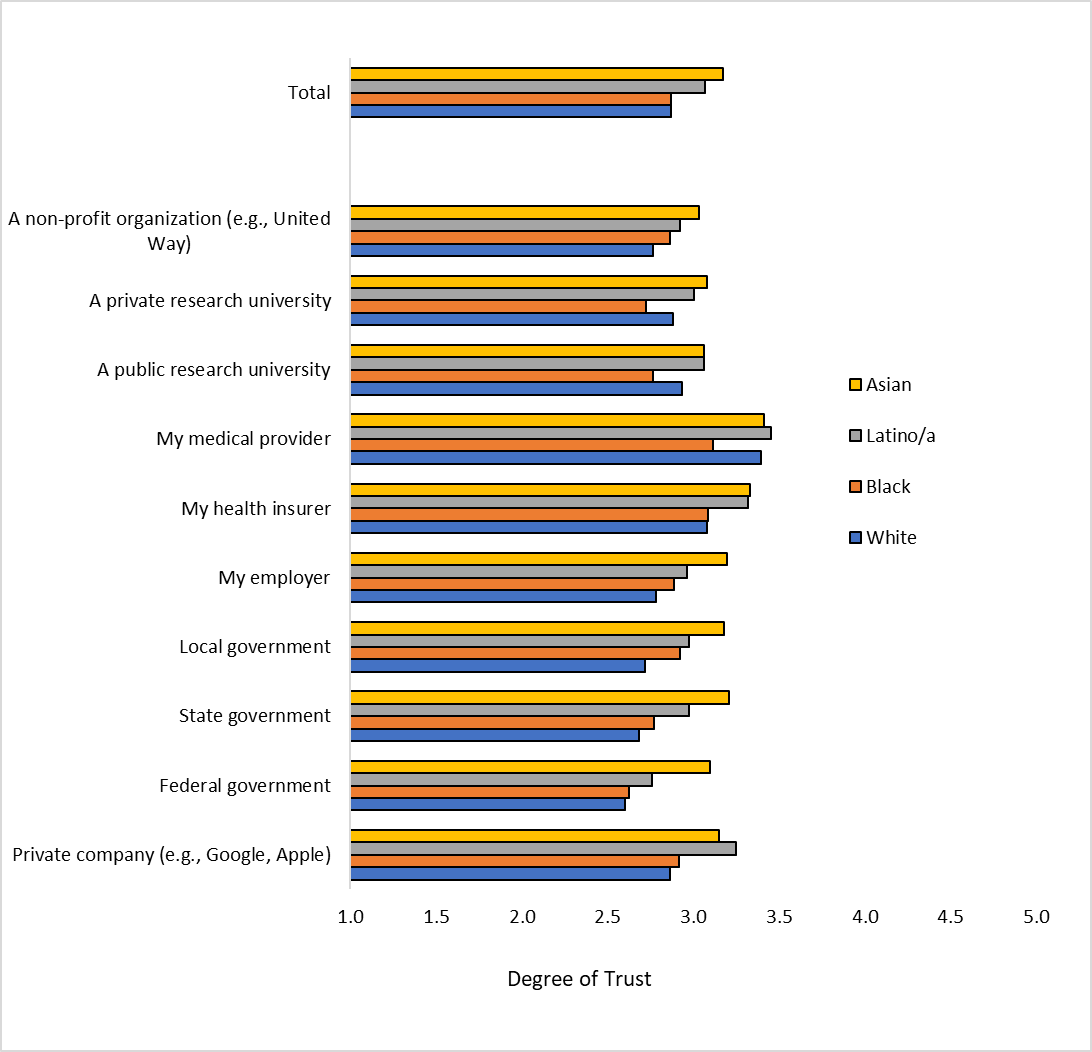

Race. Asians (M=3.18) reported the greatest degree of trust, across all organization categories, followed closely by Latinos (M=3.07) (See Figure 5). Whites and Blacks (M=2.87) tended to trust organizations less than Asians and Latinos, though Whites’ trust in their medical provider—the most trusted entity—was on par with Asians and Latinos. In convergence with past work (e.g., Gramlich & Funk, 2020), the present results suggest that efforts promoting the utilization of mobile phone technology to combat COVID-19 may be slightly more challenging among Black individuals.

Figure 5: If such a COVID-19 status app were offered, who would you trust to protect your privacy?

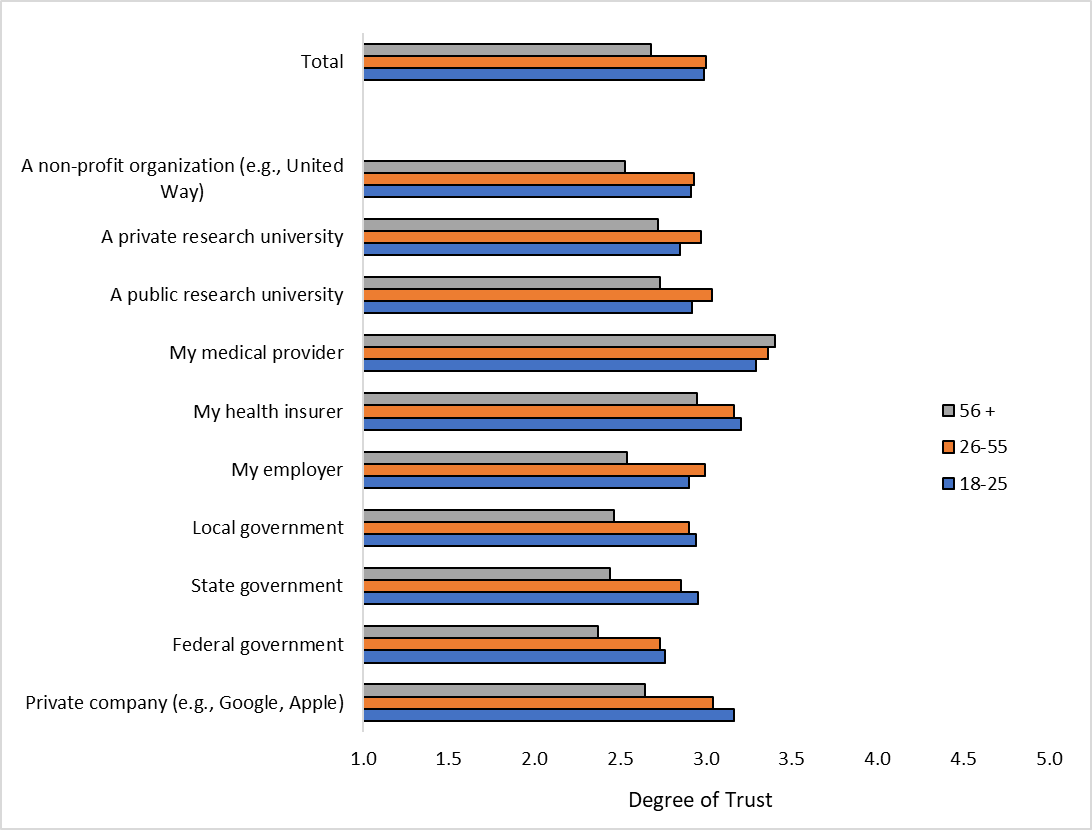

Age. Across all institutions, individuals 56 and older generally showed less trust (M=2.68) than those 26-55 (M=3.00) and 18-25 (M=2.99) (see Figure 6). Those in the 56 and older age group were most trustful of their own medical provider—which scored the highest overall trust across age groups—and placed the least amount of trust in the federal government followed closely by the state government. This sentiment was mirrored in the open-end responses and extended to those 26+. Some respondents over the age of 26 referred to a mobile phone technology to trace-and-trace COVID-19 as “Orwellian” if associated with the government. For example, one participant stated “It is way too big-brothery and is a step toward more invasive surveillance than we already experience through technology.” Perhaps not surprisingly, private tech companies like Google and Apple garnered more trust from younger age groups.

Figure 6: If such a COVID-19 status app were offered, who would you trust to protect your privacy?

Personal motivations

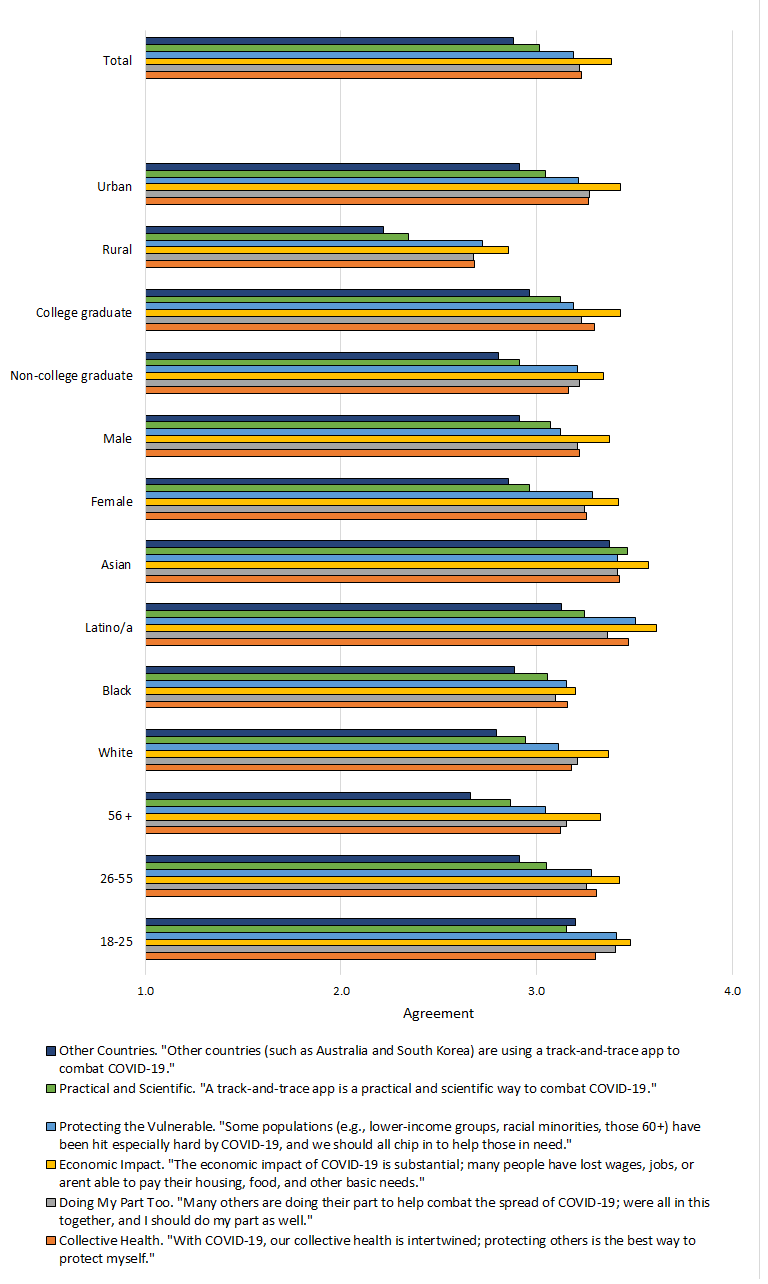

Similar to our previous analysis, we investigated how personal motivating factors predicted willingness to utilize a COVID-19 mobile app (see Figure 7). There were a few notable findings. First, respondents living in rural areas were the least compelled across all domains and were especially unconvinced by the argument that track-and-trace technologies were successfully used by other countries. Second, the economic argument was the most persuasive for every demographic group. After this, participants found the “collective health,” “doing my part,” and “protecting the vulnerable” arguments approximately equally compelling. Third, most groups, aside from Asians, found it relatively uncompelling to consider track-and-trace as a practical and scientific means to combat COVID-19. Fourth, college graduates generally found all arguments to be more compelling than non-college graduates, except for the “doing my part” argument.

Several participants noted that the logistics for an effective track-and-trace app were far too many for this to be a practical response to COVID-19. Respondents’ concerns ranged from reliable testing, adequate uptake of the mobile app, frequent updates to COVID-19 status, and even issues related to the digital divide for segments of the population lacking access to smartphones.

Furthermore, most groups were not persuaded by the fact that other countries successfully combated COVID-19 using track-and-trace technology. Respondents residing in more rural areas and 56+ years of age found this argument especially unmoving.

Figure 7: Why might you personally utilize a track & trace app?

Methodology

Participants were recruited from a panel survey conducted by Dynata, INC (https://www.dynata.com/). The sample consisted of N=1,993 individuals residing in Illinois (49.9% female, mean age=44.7, SD=16.7).

References

Anderson, M. & Auxier, B. (2020, April 16). Most Americans don’t think cellphone tracking will help limit COVID-19, are divided on whether it’s acceptable. The Pew Research Center. https://pewrsr.ch/3agh0KC.

Gramlich, J. & Funk, C., M. (2020, June 5). Black Americans face higher COVID-19 risks, are more hesitant to trust medical scientists, get vaccinated. The Pew Research Center. https://pewrsr.ch/376YXXd.